WILLIAM FAULKNER, FOREST BESS, MATSUO BASHO

"The secret of poetry lies in treading the middle path between the reality and the vacuity of the world.

– Matsuo Basho1

Meaningful art strikes us at our core. We relate to it not solely through the recognition of its subject or narrative, but also through a sense of a deeper and broader meaning. William Faulkner, the novelist, Forest Bess, the painter, and Matsuo Basho, the poet, are three artists whose work affects us on multiple levels, and stays with us long after we have left it. Since the beginning of time, artists and poets have struggled to come to terms with questions of reality, truth and purpose. Faulkner, Bess and Basho sought answers to these questions through the exploration of mankind’s relationship to nature. By exploring consciousness and using the landscape as a metaphor for existence, William Faulkner is able to touch on every aspect of human life in his novels. The reclusive artist Forest Bess, who also stayed close to the landscape, dug deep into his psyche and dreams in an attempt to find greater truths. He felt that the abstract systems and patterns of natural phenomena could be perceived through the unconscious. These ideas are not a bi-product of Modernism; in the seventeenth century the poet and teacher, Matsuo Basho, sought answers to universal questions in nature and in everyday life. I share a sense of the interconnectedness of nature and mankind with all three artists. It is the complexity of nature (defined as the space, light, form, and energy that surrounds us), and the possibility of a reciprocation of meaning and understanding that drive me to paint.

To me, William Faulkner’s writing has always felt close to painting – his book As I Lay Dying, in particular, has stayed with me. I have read and reread this novel for the past several years, and each time I find something new. It is this richness that I look for in art and strive to achieve in my own paintings. Faulkner is an abstract writer – he does not describe his characters in a literal way, but rather layers meaning through exploration of their thoughts, emotions, and actions (or lack thereof). He works from the inside out. The following passage from As I Lay Dying is especially painterly:

He did not know that he was dead, then. Sometimes I would lie by him in the dark, hearing the land that was now of my blood and flesh, and I would think: Anse. Why Anse. Why are you Anse. I would think about his name until after a while I could see the word as a shape, a vessel, and I would watch him liquify and flow into it like cold molasses flowing out of the darkness into the vessel, until the jar stood full and motionless: a significant shape profoundly without life like an empty door frame.2

In this passage there is no separation between the characters’ physical bodies, their thoughts, and the land in which they live. Faulkner captures the amorphous quality of ideas, perception, and reality through the slow and meditative quality of his words and imagery. Faulkner’s characters become metaphors for a larger sense of the cycles of life, human relationships with each other, and with the landscape. Much of this can be attributed to a deep connection to his family roots and cultural history.

Faulkner was born into an old Southern family in 1897 and remained on more or less the same land for his entire life. His novels take place in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, which was based on his hometown of Oxford, Mississippi. According to Faulkner, the name means "the water runs slow through flat land,"3 which reiterates the importance of the landscape. Yoknapatawpha County exists in the "middle path between the reality and the vacuity of the world" that Matsuo Basho referred to in his teachings and can be seen as a metaphor for how the universe grows, changes, and turns in on itself. There is no distinction between the land, the animals, and the people; they are inextricably connected.

The tilted lumber gleams dull yellow, water-soaked and heavy as lead, tilted with a steep angle into the ditch above the broken wheel; about the shattered spokes and about Jewel’s ankles a runnel of yellow neither water nor earth swirls, curving with the yellow road neither of earth nor water, down the hill dissolving into a streaming mass of dark green neither of earth nor sky.4

In As I Lay Dying, the young Vardamon catches a fish and hauls it up to the house to show his mother who, unbeknownst to him, has just died. The fish slips out of his hands and into the dust, smearing him with blood, filth and dirt. Once he discovers his mother’s death he is convinced that by killing the fish he has killed his mother. Later the fish is "cooked and et," thus completing the cycle.

Then I begin to cry. I can feel where the fish was in the dust. It is cut up into pieces of not-fish now, not-blood on my hands and overalls. Then it wasn’t so. It hadn’t happened then … If I jump off the porch I will be where the fish was, and it all cut up into not-fish now. I can hear the bed and her face. …

Vardamon runs to the stables where the horses are kept

The life in him runs under the skin, under my hand, running through the splotches, smelling up into my nose where the sickness is beginning to cry, vomiting the crying, and then I can breathe, vomiting it. It makes a lot of noise. I can smell the life running up from under my hands, up my arms, and then I can leave the stall.5

The expulsion of vomit and tears at the same time as the absorption of the energy of the horse is a powerful image that, again, breaks down any barriers between the boy and the animal. Faulkner’s use of "not" (not-fish, not-blood) effectively places us in Basho’s middle territory. Paradoxically, by asserting the thing (blood, fish) in a negative way we understand that while the thing has changed or been destroyed, it has not lost any of its original power or presence. By asserting the negative, Faulkner locates the thing in a place between creation and destruction; blood or not-blood, they carry equal weight. It is the process of creation and destruction, assertion and negation, and the ability to break down the distinctions between space and form, that is so related to painting.

Faulkner was a farmer, a hunter and a horseback rider. He spent much of his youth hanging around the horse stables where men would gather to tell stories. The exchange of impressions and the colorful personalities and relationships that Faulkner witnessed surely fed his creativity. The idea of an oral history’s being passed down through generations, growing and changing along the way, is an important aspect of his work. The tradition of oral history is related to perception and how memories grow and change with time and accumulate more impressions. Faulkner saw firsthand the changes that took place in the South in the early part of the century, as agricultural life was pushed out and replaced with modern technology. He lamented the loss of a way of life that was closely tied to the land.

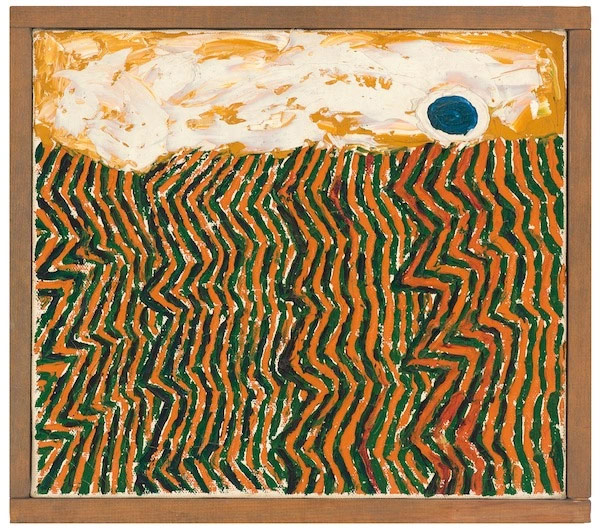

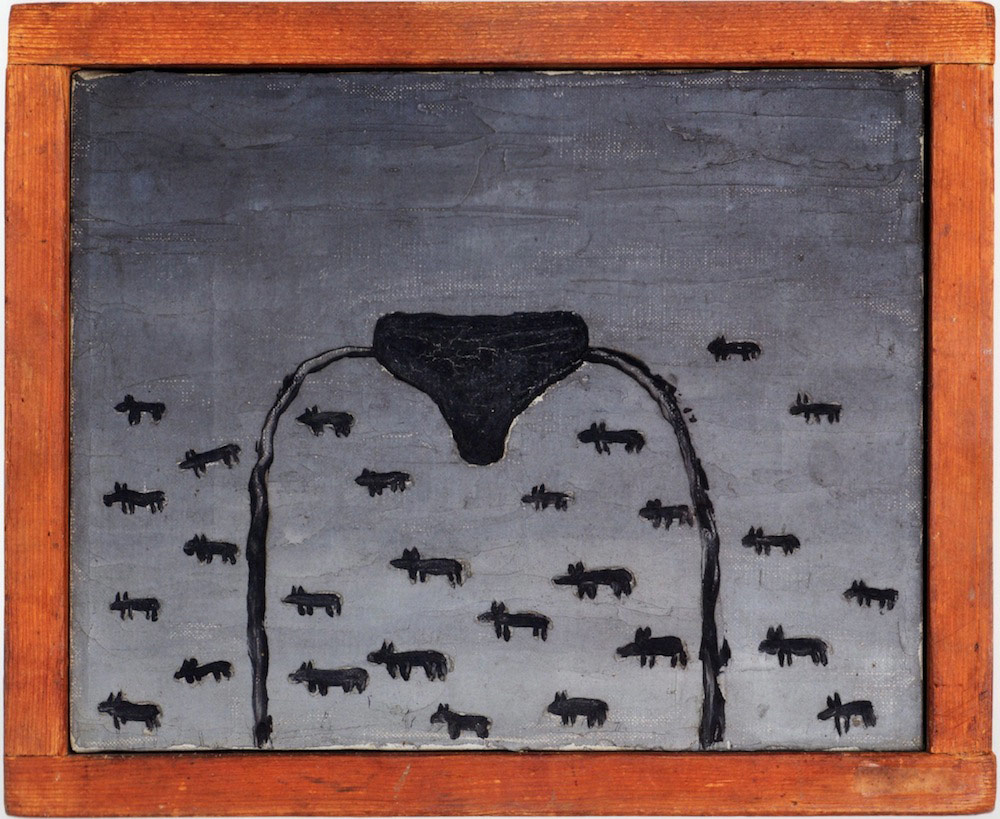

Paintings by Forest Bess

Forest Bess was an eccentric artist who, like Faulkner, was unwilling to leave the landscape of his youth. Bess would have fit right into one of Faulkner’s novels; he lived in a shack by the water in Bay City, Texas, and survived by fishing for, and selling, bait. He was born in 1911 and, from 1947 to 1961, made paintings and developed his ideas about existence and the universe. Despite some contact with the art world, including shows at Betty Parsons Gallery in New York City, and correspondence with Meyer Schapiro, he stayed in Texas. Bess thought the secret to immortality was to be found in androgyny, and even went so far as to perform an operation on himself. The androgyne, who combines male and female in a single being, can be seen as an embodiment of the breaking down of divisions. By extension, the idea can be interpreted as seeing yourself as part of a whole instead of as a separate, autonomous entity. I feel that meaningful art is created when you cease to see the divisions between yourself and nature or between yourself and the painting.

This idea of breaking down divisions was described by the seventeenth century Japanese poet Matsuo Basho. In his teachings on Haiku he stated, "One must first of all concentrate one’s thoughts on an object. Once one’s mind achieves a state of concentration and the space between oneself and the object has disappeared the essential nature of the object can be perceived."6 Basho lived a life of wandering, writing, and teaching poetry in Japan in the latter half of the seventeenth century. Basho, along with two other Haiku masters that were of later generations, developed the Haiku form, or Hokku, as it was initially called. Important aspects of the form: attention to time and place, a subject rooted in the common life, and a plainness of language. Following are some examples of his Haiku in which he gives a sense of the interconnectedness of all things through observations of ordinary events.

Autumn moonlight—

a worm digs silently

into the chestnut.

Awake at night—

the sound of the water jar

cracking in the cold.

Early fall—

the sea and the rice fields

all one green. 7

Staying close to traditional themes such as seasons and nature gives a "powerful sense of a human place in the ritual and cyclical movement of the world."8 It was these cycles that Forest Bess sought to tap into through his paintings. These ideas of ritual and cycles, and the close connection (across time) between humans and nature, can also be found in the theories of Carl Jung. Bess was an avid reader of Jung and felt that the imagery in his dreams was coming directly from what Jung referred to as the "Collective Unconscious."

Carl Jung, born in 1875, was fascinated by folklore and myths. In his studies of different cultures, he was struck by the universality of many themes, images, and stories. He found that similar, even identical, images often appeared in the dreams of his patients. It was out of these observations that his theory of the collective unconscious was developed. Jung felt that the unconscious consisted of two layers: the personal unconscious and the collective unconscious. The personal unconscious consists of individual experiences and memories that have been forgotten and/or repressed. The collective unconscious is the deeper layer, and is not individual, but universal. It has "contents and modes of behavior that are more or less the same everywhere and in all individuals."9 Bess believed that the unconscious was capable of perceiving underlying patterns and movements found in nature. He stated, "I was only a conduit through which this thing, whatever it was, flowed."10 While he felt his imagery came directly from this "Collective Unconscious," a more likely scenario is that his imagery emerged out of a heightened sensitivity to the phenomena of nature (see Figs. 1-5). This sensitivity, combined with a deeply troubled sense of self, and a sexuality that he couldn’t come to terms with, led to the creation of very moving paintings.

William Faulkner felt that the way to truth was through "writing about people. About man as he faces the eternal truths of love, compassion, cowardice, protection of the weak. Not facts, but truths. … Man as he comes in conflict with his heart."11 Much of the power of Bess’s work lies in this conflict: its honesty, its authenticity and its search for answers. John Yau, poet, and art critic, attributes the intensity of the work to its lack of irony and lack of concern with covering up the scars and the pain of Bess’s experience.12 Bess firmly believed that he was after something larger and more universal than his individual existence. In a letter to Betty Parsons, he said he felt a deep longing to unite long lost parts of himself.13 He sensed a deep connection to the land, and he wanted to be both a giver and a receiver. He sensed the possibility of a reciprocal relationship with the abstract structure of nature.

Bess was right in his sense that the unconscious is better able to perceive abstract patterns in nature. When we are sleeping or in a meditative state, we have relinquished control. In everyday life and consciousness we relate to the world with a set of established ideas about how things are and how they should be. We impose our ideas on the world around us, rather than allowing ideas to come to us through nature. If we can break down our assumptions, we can heighten our perceptual sensitivity to the world. The artwork of children is so fascinating because of its honesty and lack of self-consciousness. Similarly, we are moved by cave paintings created 30,000 years ago because the imagery was not created with the burden of art history and ideas of what "good art" is, or even what "art" is. Matsuo Basho says to the poet (or artist): "Learn about pines from the pine, and about bamboo from the bamboo. Don’t follow in the footsteps of the old poets, seek what they sought."14

Most beginning artists feel that making art is about copying or describing what you see, in a sense freezing the moment in time on a sheet of paper or a piece of canvas. One of the first lessons of drawing from life is trusting in your perception enough to not draw what you think is there, but what you actually see and feel. One of the biggest challenges in painting is to relinquish control and do away with established ideas about how things should be or look. As soon as the intellect takes over and attempts to fit your perceptions and experiences into existing molds, the truth of the experience has been lost. Matsuo Basho states that: The basis of art is change in the universe. What’s still has changeless form. Moving things change, and because we cannot put a stop to time, it continues unarrested. To stop a thing would be to halve a sight or sound in our heart. Cherry blossoms whirl, leaves fall, and the wind flits them both along the ground. We cannot arrest with our eyes or ears what lies in such things. Were we to gain mastery over them, we would find that life of each thing had vanished without a trace.15

As soon as you try to control nature or understand it in a linear way, you are blocked from a true understanding. Similarly, William Faulkner stated, "fiction that is worth anything necessarily fails to embody what cannot be embodied, to tell a story and reflect a consciousness that cannot be told or reflected except partially, by hints and guesses."16 He seems to be illustrating this point in As I Lay Dying. The fact that the story is told through 59 interior monologues, suggests that it is impossible to get the whole story through one point of view, if at all. And yet, ironically, this is what artists set out to do.

Bruce Gagnier, in a slide talk at the New York Studio School, remarked that the "secret is in the sketch." When artists are sketching, they are not concerned with the final product, they are not trying to pin anything down. They are trying to capture their experience in the most direct way possible and are not concerned with the "right" or "wrong" way. The drawing remains open and, as a result, more truthful to the experience. Once you are in the appropriate state of concentration to perceive the essential nature of your experience, Basho says you must "express it immediately. If one ponders it, it will vanish from the mind."17 William Faulkner wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks, with little to no revision, and often with no concern for accepted modes of sentence structure, spelling, and punctuation. The end result is a book that, in my opinion, comes as close as a work of art can come to "naming the unnamable."

In my own work I struggle with all of these issues. I try to find the balance between intuition and intellect, so that the process of painting becomes an active dialogue with the phenomena of nature. While I do not paint directly from the landscape or model, and my paintings are non-objective, I consider myself a perceptual painter. Perception is not simply the linear collection of sensory data; rather it expands and contracts in all directions. It includes established feelings about, and memories and associations related to, what is being perceived, as well as new ideas formed simultaneously. Perception is sensitivity to the subtleties of nature and of our experience within nature. It is through heightened perception that we are able to reach Basho’s middle ground.

Much of my painting is done away from the canvas, whether I am running along the Westside Highway, driving up Third Avenue, or, like Bess, lying in bed close to sleep. Running, like sleep, is a way to suppress the intellectualization of perceptual experience. In the midst of a long run, the body takes over and the brain becomes focused in a way that is similar to meditation. One of my favorite runs is along the Westside Highway. Running with cars speeding by on one side and helicopters landing on the other, is a truly exhilarating urban experience that mirrors Basho’s constantly shifting universe. All of the contradictions of nature can be found along the Westside Highway – the speed of the cars and the gentle lapping of water, the extreme geometry of the buildings circled by ribbons of highway, and vegetation growing over construction fences. I am struck by the dilapidated piers and pilings, and the garbage and foam that washes up along the rocks. It is this place where nature and manufactured life meet, the collision of ideas with form, where painting happens.

In a successful work the paint has been transformed into an idea borne out of the dialogue between the artist and nature. There is special power and intrigue in deterioration and ruins. I see them as a bridge between the natural and the man-made. Ruins are a metaphor for the cycles of life, the struggle to sustain one’s vision. The ruins of industry bear witness to the reclaiming of power and the assertion of nature (space, light, energy, form). Ruins are, in a sense, what paintings are: places in between creation and destruction, between the controlled and the accidental. The same focus that happens while running happens while driving in New York City. The cars move in and out according to a unique set of rules – if you hesitate or think twice before changing lanes you will crash. You have to be tuned into this unique system and anticipate your next move almost at the exact time of action.

Similarly, when painting in the studio, there can be no hesitation. I try to achieve the kind of focus necessary to "make the space between oneself and [the painting] disappear" by beginning with memories.18 Memories are a direct route to a more honest and felt experience because they are already so abstract and full of (intellectual) contradictions. They are what Faulkner would call not-events: events that have taken place and have the added information of feeling, association and experience. They are often illogical, and yet they are acceptable as vivid and real. I begin with memories of events, feelings or colors – the pink of my favorite childhood bathing suit, the first time I told a lie. In the process of sorting through the detritus of past perceptual experience, the paintings become layered with associations and other memories are uncovered. It is not unlike digging in the dirt and the paintings are redolent of earth. Often the initial idea needs to be lost so it doesn’t interfere with what the painting itself is telling me. Despite having been lost, the initial idea ultimately returns in an unexpected way. The paintings are a battle between controlled decisions and intuition. It is only when intuition has taken over and the paintings have become living, breathing tissue, that they are complete.

In conclusion, painting is about breaking down barriers and exploring the unknown. It is about searching for answers to elusive questions about our relationship to the world and to the people around us. Faulkner, Bess, and Basho are three artists who, I believe, managed to tread the middle ground between reality and vacuity, or the known and the unknown. They did this by staying close to nature and close to the everyday life that they knew best. I, like Faulkner, Bess, and Basho, sense an underlying system, an inseparability of human consciousness and nature. It is the possibility of reciprocation of energy and understanding between the artist and natural phenomena that drives me to paint. By staying close to personal feelings and memories, I hope to create honest and authentic work that can be related to without the requirement of prior knowledge of the feelings or events depicted. Finally, I feel that it is my responsibility to continue to search and explore consciousness and the phenomena of nature through the "partial reflections" and "hints and guesses" to which Faulkner so aptly referred.

Becky Yazdan, MFA Thesis 2005

REFERENCES

1 Robert Hass, ed. The Essential Haiku: Versions of Basho, Buson & Issa. (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc, 1944) 234.

2 William Faulkner, As I Lay Dying (New York: Vintage International, 1930) 173.

3 Jay Farini, One Matchless Time: A Life of William Faulkner (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc, 2004) 1.

4 Faulkner 49.

5 Faulkner 53-54.

6 Hass 234.

7 Hass 12, 19, 24.

8 Hass xiii.

9 Charles Harrison & Paul Wood, eds, Art in Theory 1900 – 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas (Malden: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2003) 378-379.

10 Barbara Haskell, Forest Bess, exhibition brochure (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1981), unpaginated.

11 Farini 399.

12 Chuck Smith & Ari Marcopolous, Forest Bess: Key To The Riddle (New York: Smith/Marcopolous Productions), RT: 00:47:30.

13 Smith.

14 Hass 233.

15 Hass 233.

16 Farini 115.

17 Hass 234.

18 Hass 234.